Co-Teaching as a Mechanism to Deliver Specially Designed Instruction as Part of Special Education Services Within the Context of the General Education Setting

Dr. Tammy Barron

Example 1:

Co-teaching occurs when two or more professionals jointly deliver substantive instruction to a diverse, blended group of students, primarily in a single physical space. Co-teaching involves embedding special education service within general education lessons with both teachers actively contributing to the instruction of their shared students. One example is using parallel teaching to increase student learning by having each teacher responsible for only part of the class. In this approach, students are divided into two groups for instruction. Parallel teaching in its most basic form has the teachers assign students to one group or the other, usually heterogeneously but also sometimes deliberately. For example, several students with behavior problems are likely to be split across the two groups. Students who tend to productively contribute to any activity likewise might be split across the two groups.

The instruction that occurs is identical in terms of overall goals, possibly a test review or discussion of the literature being read or chapter being studied. This co-teaching approach also can be used to tier instruction, that is, to provide instruction on the same concepts at higher and lower levels or to engage students in producing different products. If both teachers are knowledgeable of the content. Another use of parallel teaching is to introduce students to perspective, point-of-view, or alternative methods, later bringing students together to debate or teach one another.

The key to using parallel teaching effectively is to explore its versatility by first using it in basic ways and then creating variations that work for a particular student group. Specially designed instruction is most likely to be incorporated when groups are skill-based, but practice on skills already taught can usually be arranged as part of this co-teaching approach.

(Adapted from Friend & Barron, 2021)

Co-teaching helps support students’ access to the general curriculum and offers a way to close the gap between the achievement and other outcomes of students with disabilities and those of their peers. Co-teaching evolved from the inclusive practices movement and is supported by federal law and guidance regarding the least restrictive environment (LRE) and participation in general education.

Co-teaching provides access to the general curriculum as deemed essential for nearly all students. It also addresses the interpretation of IDEA that the least restrictive environment for most students should be a general education classroom (Friend, 1993; Friend & Barron, 2021). Ultimately, co- teaching is proposed as the most likely route for closing the achievement gap between students with disabilities and their typical peers. Thus, co- teaching programs now are established in elementary, middle, and high schools and are implemented across subject areas (Friend, 2019).

Example 2:

In alternative teaching, one teacher instructs most of the students while the other teacher works with a small group at the side or in the back of the classroom. The small group may be receiving essentially the same instruction as the larger group. For example, the same math concept may be introduced, but the small group uses manipulatives that the rest of the class does not need. The instruction may also be targeted to specific student needs, as when one teacher reads aloud with some students and other students are reading independently. This co-teaching arrangement may last the entire co-teaching time or class period, or it may be an approach used only for a few minutes of a class session, often at the beginning (for example, during a warm-up or check of homework) or end (for example, as other students begin practice work or an assignment).

The key to effectively implementing alternative teaching is to carefully determine the purpose for the small group and the students who should participate in it. For example, in some situations students benefit from re-teaching or remedial work that is best carried out in the small group. Alternatively, they may need enrichment or extension. Yet another purpose of the small group is to assess students’ mastery of key concepts. Occasionally, the small group might even be used to directly address the IEP goals of students with disabilities or the language goals of students learning English. Co-teachers should also make a plan for deciding which of them instructs the alternative group.

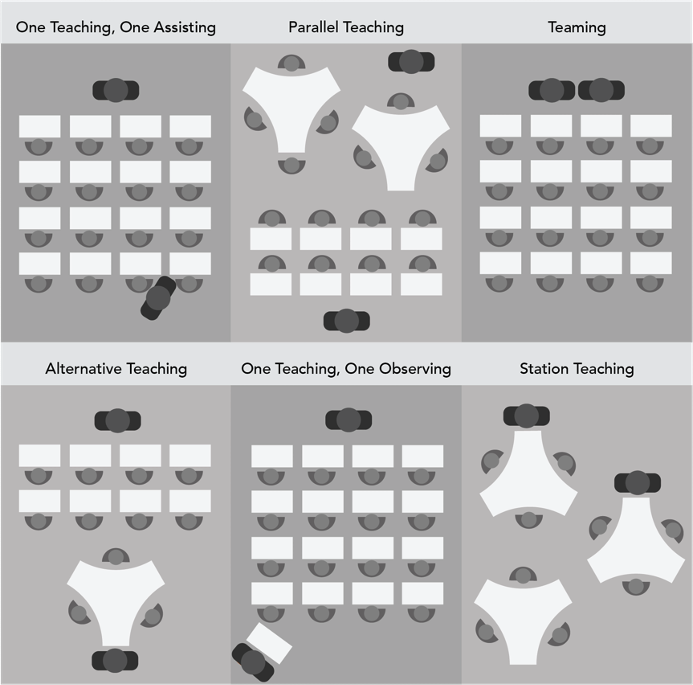

Co-teachers generally are familiar with the six classic co-teaching approaches:

- One teach, one observe (one teacher leads while the other gathers data)

- Station teaching (three groups, two with teachers and one independent, with each station repeated for each group)

- Parallel teaching (two groups, one for each teacher and with no rotation)

- Alternative teaching (most students with one teacher while the other works with a small group)

- Teaming (teachers sharing instruction for the whole group)

- One teach, one assist (one teacher leads while the other supports individual students)

Co-teaching teams also know that their goal should be to use station teaching, parallel teaching, and alternative teaching most of the time to maximize the impact of having two teachers in the classroom (Friend, 2019).

Steps to implement co-teaching in your school:

- Seek professional development for all faculty and administrative staff to build a solid understanding of co-teaching roles and responsibilities. Teacher knowledge is an important factor to effective implementation.

- Determine the students who will be included and served in the co-taught classrooms.

- Establish clear structures that support co-teaching, including but not limited to changes in the master schedule, protected planning time for teachers, and a way of coaching and providing feedback to co-teachers.

- Leaders set the direction and address buy-in from teachers. The belief that co-teaching allows students to be well supported in inclusive environments must be established.

- Develop parity between co-teaching partners in the classroom through effective communication and collaboration.

- Develop problem-solving protocols that can be used by teams to reflect on and improve co-teaching practice over time.

- Assess to determine what is working and what needs improvement. Remember co-teaching is a service delivery model for special education and is not merely a teacher preference. It is giving students what they need!

Utilizing co-teaching for the delivery of special education services is to ensure that students with disabilities do not miss learning opportunities as happens when they leave the general education setting for separate instruction. The belief system of inclusiveness argues that removing any student from a general education environment should be a strategy of last resort and include a careful analysis of costs to the student as well as benefits.

Matters related to the quality of the overall instruction, teachers’ skill in embedding specially designed instruction into lessons, and logistics such as the scheduling of students and teachers must be tackled. Co-teaching requires a high level of teacher collaboration and planning in order to be sustainable, and so it merits continued, intensive attention to characteristics of collaboration that currently are too seldom undertaken. Some tips to address these roadblocks include:

- Practice exemplary collaboration skills in routine situations. If you focus on clear communication and step-by-step problem solving while working with a colleague with whom mutual trust and respect have already been established, when a situation is stressful or awkward, you will be more likely to respond in a way that is constructive. In challenging situations, take a moment to think before speaking, to ask questions before stating opinions, and to paraphrase to check that you heard another’s perspective accurately.

- Clearly identify with your teaching partner(s) your roles and responsibilities even if you are an early career special educator and hesitant to negotiate about this. Remember that some general educators may only learn about co-teaching through your contributions, as it is not required in all teacher preparation programs, and some districts may not provide related professional development. By clarifying why you are assigned to co-teach and what your areas of strength are, you can ensure that students receive the embedded specially designed instruction that is the purpose of co-teaching.

- Be an advocate of the practice by keeping it child-centered. If the service option is conceptualized as the general practice of differentiation (which is a responsibility of all teachers) or the provision of students’ accommodations (which, in general education, is primarily the responsibility of the general educator), SDI is not in place and students are not receiving the tailored Instruction that will accelerate their learning. Learn how to share the value of co-teaching practice.

(Friend & Barron in McLeskey, J., Barringer, M-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., Lewis, T., Maheady, L., Rodriguez, J., Scheeler, M. C., Winn, J., & Ziegler, D. (2017)

Linked Resources:

Council for Exceptional Children: Successful Co-Teaching https://www.cec.sped.org/News/Special-Education-Today/Need-to-Know/Need-to-Know-CoTeaching

Research Studies on the Topic:

Conderman, G. G., & Liberty, L. (2018). Establishing parity in middle and secondary co-taught classrooms. Clearing House, 91, 222–228.

Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (2017). Making inclusion work with co- teaching. Teaching Exceptional Children, 49, 284-293.

Walsh, J. M. (2012). Co-teaching as a school system strategy for continuous improvement. Preventing School Failure, 56(1), 29-36.

Wexler, J., Kearns, D. M., Lemons, C. J., Mitchell, M., Clancy, E., Davidson, K. A. ., …Wei, Y. (2018). Reading comprehension and co-teaching practices in middle school English language arts classrooms. Exceptional Children, 84, 384–402.

Position Papers or Practitioner Publications:

Friend, M. & Barron, T.L. (2021; 2017). (Chapter: Collaboration High-Leverage Practices). In McLeskey, J., Barringer, M-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., Lewis, T., Maheady, L., Rodriguez, J., Scheeler, M. C., Winn, J., & Ziegler, D. (2017). High- leverage practices in special education (pp. 27-30). Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center.

Carty, A., & Farrell, A. M. (2018). Co-teaching in a mainstream post-primary mathematics classroom: An evaluation of models of co-teaching from the perspective of the teachers. Support for Learning, 33, 101–121.

Fitzell, S.G. (2018). Best practices in co-teaching and collaboration: The HOW of co- teaching—-implementing the models. Manchester, NH: Cogent Catalyst Publications.

Hedin, L., & Conderman, G. (2019). Pairing teachers for effective co-teaching teams. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 55, 169–173.

Level of Evidence:

Validated. Research suggests that students with disabilities who stay in general education settings outperform those who receive separate services (e.g., Tremblay, 2013; Wexler et al., 2018). The result is found regardless of student disability labels, ages (grades 3-8), and other demographics (Cole et al, 2019). Finally, the bedrock belief system of inclusiveness argues that removing any student from a general education environment should be a strategy of last resort and include a careful analysis of costs to the student as well as benefits.