Young children with disabilities often struggle with language acquisition and communication. Dialogic Reading (DR) can improve students’ language and communication (Coogle, 2020; IES, 2010) as well as vocabulary and reading comprehension (Doyle & Bramwell, 2006).

DR, developed and first described by Whitehurst (1988), is a type of shared storybook reading that promotes conversation and interaction between the reader and the listener through strategic questioning and prompts (Doyle & Bramwell, 2006; Whitehurst, 2002). In Dialogic Reading, the adult reader and child listener change roles, promoting the child’s ability to function as a storyteller with the adult participating through active listening and questioning (IES, 2010). Because DR can be used in shared reading experiences with books on any topic, it is also an excellent tool to expand vocabulary learning and comprehension in interdisciplinary contexts (Doyle & Bramwell, 2006).

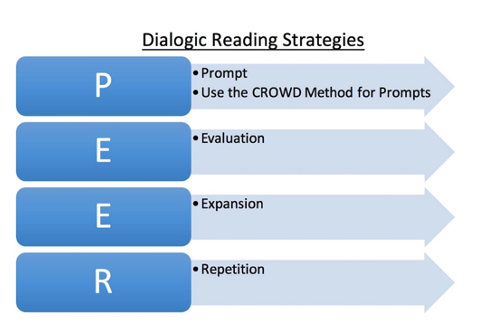

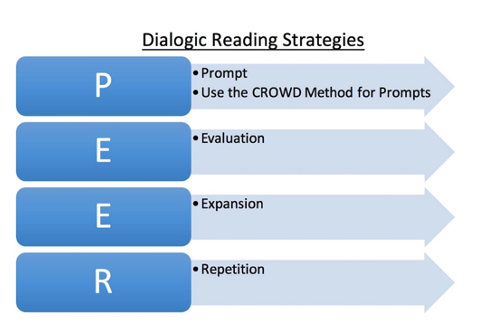

The primary strategy to support student learning during DR is the PEER sequence. The PEER sequence promotes adult child interaction and should be used throughout the shared reading experience. In the PEER sequence (See Figure 1), the adult reader: Prompts the child to say something about the book; Evaluates the child’s response; Expands on the child’s response using rephrasing and extension, and; Repeats the child’s response to ensure learning (Whitehurst, 2002; IES, 2010).

To support the prompting component of the PEER sequence, the CROWD method is suggested as a useful strategy. The CROWD method provides adult-initiated, scaffolded categories of prompts, including: Completion prompts, Recall prompts, Open-ended prompts, Wh-prompts, and Distancing prompts. Whitehurst (2002) notes that the recall and distancing prompts are more difficult and complex than completion, open-ended, and wh- prompts, and should be used sparingly with preschool and kindergarten aged children. However, through repeated readings of a text, increasingly higher-level prompts can be used to scaffold student learning (IES, 2010; Doyle & Bramwell, 2006). Figure 2 provides descriptions of each prompting type represented in the CROWD Method, as well as an example for each.

One strategy for implementation suggested by The Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR) (n.d.) is breaking up DR into a five-day sequence with a single book. The five-day progression allows teachers to provide repeated experiences with a text while implementing elements of both the PEER sequence and the CROWD method. A five-day DR Lesson Plan Template is linked to this brief, as well as video exemplars of what the implementation of a five-day sequence would look like in the classroom.

While DR can be used with a large group of children, it has been found to be especially effective for use in small groups (FCRR, n.d.; Doyle & Bramwell, 2006). The small group setting allows for increased active participation from students and enables the teacher to differentiate instruction in more meaningful ways. For example, within the small group setting, a teacher can use different types of prompts from the CROWD method to meet individual student needs. Small group dialogic reading also provides the teacher with opportunities to build and strengthen relationships with students that can positively impact learning (Doyle & Bramwell, 2006; FCRR, n.d.).

Before beginning DR in the early childhood classroom, Doyle and Bramwell (2006) recommend that teachers consider the logistics of implementation. Since DR is most effectively conducted in a small group setting, teachers must consider how children will be grouped, when the groups can be conducted, and who will supervise students when the teacher is conducting groups.

When first implementing DR, the use of familiar texts can be beneficial to help teachers build their own skills as dialogic readers (Doyle & Bramwell, 2006). By using books with which they are already familiar, teachers can reflect on the DR process and questions used during instruction. Teachers may need to consider what types of questions promote the most engagement, the number of questions to ask during each reading, and how to scaffold the questioning during repeated readings.

Planning to meet the needs of individuals and small groups can also promote effective DR implementation and student learning. Towson et al. (2016) recommend that thoughtfully targeting vocabulary that meets the receptive and expressive language needs of each individual/group.

An initial roadblock to implementation of DR would be logistical or procedural limitations like scheduling, classroom supervision issues, or ability of the teacher to conduct multiple small group DR lessons each day. Fortunately, DR is an instructional method that does not require a licensed teacher for successful implementation. Trained paraprofessionals, classroom volunteers, and parents can assist with implementation with positive results (Towson et al., 2020; IES, 2010).

For teachers required to follow a specific curriculum or pacing guide, the repeated readings across multiple days required to effectively implement DR may present a roadblock. To mitigate this issue, conducting the DR lessons as a classroom center or as an option on a choice board may be a solution. Planning for multiple groups of students could also be potentially prohibitive to teachers because of time constraints and other classroom responsibilities. While planning templates and similar texts can be used for multiple small groups, specific vocabulary should be targeted and questions planned to meet individual needs

Linked Resources:

Dialogic Reading: An Effective Way to Read Aloud to Young Children

Read it Again! Benefits of Reading to Young Children

Dialogic Reading Lesson Plan Template.docx

FCRR Module 1: Dialogic Reading

Book Selection for Dialogic Reading

Research Studies on the Topic:

Coogle, C. G., Parsons, A. W., La Croix, L., & Ottley, J. R. (2020). A Comparison of Dialogic Reading, Modeling, and Dialogic Reading Plus Modeling. Infants & Young Children, 33(2), 119–131. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0000000000000162.

Towson, J. Al., Fettig, A., Fleury, V. P., & Abarca, D. L. (2017). Dialogic reading in early childhood settings: A summary of evidence base. Topics of Early Childhood Special Education, 37(3), 132—146.

Towson, J. A., Gallagher, P. A., & Bingham, G. E. (2016). Dialogic reading: Language and preliteracy outcomes for young children with disabilities.Journal of Early Intervention, 38(4), 230-246. doi:10.1177/1053815116668643

Whitehurst, G. J., Falco, F. L., Lonigan, C. J., Fischel, J. E., DeBaryshe, B. D., Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., & Caulfield, M. (1988). Accelerating language development through picture book reading. Developmental Psychology, 24(4), 552-559. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.24.4.55

Level of Evidence:

The level of evidence for DR can be rated as between promising and validated, as there is quite a bit of research across a variety of contexts but there have not been studies which have been replicated. DR has been shown to enhance vocabulary and oral language in young children (Arnold et al., 1994; Coogle et al., 2020; Grolig et al., 2020; Towson et al., 2017) and to be effective in varied settings (Brannon & Dauksas, 2014; Grolig et al., 2020; Towson et al, 2017). Towson et al. (2017) found in a meta-analysis that implementation of DR differed across studies and the implementation impacted the short-term and long-term effects of the method. Results have often been mixed in both the short- and long-term, as well as in the sample utilized (children with special needs or those without) (Coogle et al., 2020; Towson et al., 2017; Towson et al., 2016). Therefore, the need for more consistent research with standard implementation protocols to determine effectiveness is warranted.