The Problem:

Educators struggle with how to teach literacy skills to students with significant intellectual disabilities (Cooper-Duffy et al, 2010). First, students with significant intellectual disability demonstrate specific learning characteristics such as difficulty attending to stimuli, memory problems, generalization, self-regulation, problems with observational learning, and synthesizing skills (Westling & Fox, 2009). Second, many educators do not know how to teach literacy skills to this population including the Extended Content Standards (Browder et al., 2008; Cooper-Duffy et al, 2010). Third, many students communicate nonverbally making it difficult to know how to teach phonological awareness and vocabulary instruction (Koppenhaver et al., 2007). Furthermore, knowing how to adapt reading and phonics instruction for learners who have multiple disabilities challenges educators (Browder et al., 2008). Students must become active readers before they become independent readers.

A Brief Overview:

Story-based lessons are used in conjunction with systematic instruction to teach literacy to students with severe intellectual and multiple disabilities. The premise behind this method of teaching literacy is derived from shared story activities whereby the teacher reads a story to a group of students and leads a discussion of themes, vocabulary, and events of the story (Browder & Spooner, 2011). Shared story reading is an interactive read aloud that promotes student active engagement rather than passive listening with the teacher prompting systematically. The shared story reading experience involves students purposefully and strategically interacting with both the content of the book and the teacher before, during, and after the read aloud. For shared story reading to be successful for students with moderate and severe intellectual disability, adaptations and accommodations are designed and implemented to meet the unique needs of this population (Browder & Spooner, 2011). This includes adapting books to be accessible while still being age appropriate, as well as developing story-based lessons that incorporate evidence-based practices (e.g., task analytic instruction, systematic prompting and feedback) into the lessons (Browder & Spooner, 2011)

Steps Toward Applying the Strategy:

Teachers must

- Select the story-based lesson for the grade level of student (Elementary, Middle or High school)

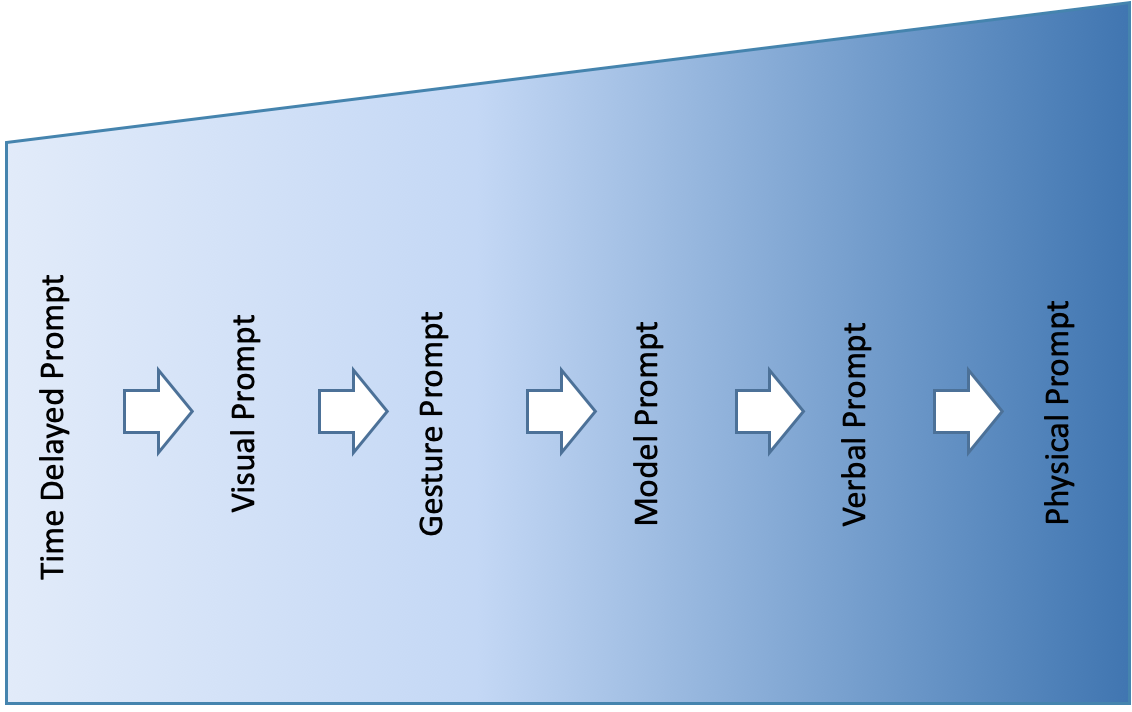

- Select 3-4 prompts for the prompting hierarchy that are needed for the specific characteristics of the students using the system of least prompts (e.g., gesture, picture, specific verbal, nonspecific verbal, model, physical).

- Prompt each step of the story-based lesson consistently using the system of least prompts until the student responds. Specifically, the teacher implements each step of the task-analysis using a least intrusive prompting strategy (e.g., allow student to answer independently, then if needed provide a verbal prompt, then if needed provide a model prompt, then if needed provide a physical prompt) (Jimenez & Kemmery, 2013). If the student was correct, specific verbal praise was provided. If the student makes an error, the teacher provides the next level of prompting to correct the error.

- Score the task analysis to note if the teacher completed the step correctly (+) or did not complete the step correctly (-) on the story-based task analysis and score if the student responded correctly (+) or incorrectly (-).

Initial Data:

The growing body of research suggests specific benefits for this population include increase in responding of students to the literature, increase in communication skills, and promotion of listening comprehension (Browder et al, 2008; Hudson & Test, 2011; Jimenez & Kemmery, 2013).

How Will This Solve The Problem?

The use of story-based lessons and the system of least prompts provides teachers with an effective and efficient method for teaching literacy to students with severe disabilities. This strategy is effective for addressing the learning challenges for students with severe disabilities and can be adapted to meet the needs of learners who communicate nonverbally.

Potential Roadblocks:

- If teachers do not use good procedural fidelity with the story-based lesson and the system of least prompts the effectiveness of the intervention can be reduced.

- Teachers may need to collaborate with general education teachers to ensure the literacy materials (e.g. types of books, graphic organizers, etc.) are on grade level for the learners with severe disabilities.

- Teachers may need to collaborate with librarians, IT specialists, occupational therapists, and speech and language pathologist to provide adequate adaptations and modification for the literacy materials so students can access literacy skills based on the extended state standards.

Level of Evidence:

The literature was used to determine the level of evidence on shared story reading using story-based lessons with the system of least prompts to promote literacy for students with severe disabilities (Hudson & Test, 2011). Aquality indicator checklist to determine research quality and standards to establish level of evidence was used with a strong, moderate or potential scale. Based on the number and quality of the research reviewed, a moderate level of evidence was found for using shared story reading to promote literacy for students with extensive support needs (Hudson & Test, 2011).

Resources

Story Based Lesson Task Analysis for Elementary School Students

| Teacher Action | Teacher Result | Student Reaction | Student Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher provides an opening attention getter that gains the students attention. Teacher prompts the student to engage with the bubbles. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student looks, touches, reaches or uses vocalization or Augmentative or Alternative (AAC) communication to interact with attention grabber. Student touches a bubble. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher gives students an opportunity to independently explore the book for one minute. Teacher prompts the student to flip through the pages. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student looks through the book for one minute. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher provides each student with 12 vocabulary words and reviews each vocabulary word with students, using prompting (zero-time delay) | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student looks, points, or says the twelve vocabulary words. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher asks each of the students to identify all the vocabulary words. Teacher calls out each word and waits for 5 s before prompting students to point or say the vocabulary word. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student looks, points, or says, to identify twelve vocabulary words. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher asks students “What do you think the book is about?” Teacher provides the students with a vocabulary picture sheet, waits 5 s before prompting the students to point or say a prediction. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student looks, points, or says a prediction. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher reads the title and ask student to point to the title, then waits 5 s before prompting students to point to the title. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student looks at or touches the title of the book. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher asks the students “How do we get started?” and waits for 5s before prompting students to turn to the first page. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student turns to the first page of the book. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher asks the student to read the repeated line, then waits 5 s before prompting students to point to a re- peated line and say or activate AAC to say repeated line (zero-time delay) | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student reads text or repeated line. The student points to the repeated line and says or activates AAC. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher gives the students the opportunity to turn the page independently, then waits 5s before prompting students to turn the page. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student turns the page of the book when appropriate. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher pauses at least once during the story to ask students to find vocabulary word or symbol in the book, then waits 5 s before prompting students to point to word or symbol. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student points, says, or looks at correct vocabulary word/picture. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher asks first comprehension questions and waits 5s before prompting student to say or point to answer. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student points, says, or looks at correct answer. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher asks second comprehension questions and waits 5s before prompting student to say or point to answer. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student points, says, or looks at correct answer. | ⊕ ⊖ |

| Teacher asks third comprehension questions and waits 5s before prompting students to say or point to answer. | ⊕ ⊖ |

The student points, says, or looks at correct answer. | ⊕ ⊖ |

Figure 1. Story Based Lesson Task Analysis for Elementary School Students (Hyer & Cooper-Duffy, 2019)

Note. Column 2: + = Teacher completed the step correctly; – = Teacher did not complete the step correctly. Column 4: + = student completed the step correctly and independently; – = student did not complete the step correctly or independently.

Source. Adapted from the story-based lesson task analysis by Browder, Trela, and Jimenez (2007).

Prompt Hierarchy from Least to Most

Studies on the Subject:

Browder, D., Mims, P., Spooner, F., Ahlgrim-Delzell, L., & Lee, A. (2008). Teaching elementary students with multiple disabilities to participate in shared stories. Research & Practices for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 33, 3-12.

Browder, D. & Spooner, F. (2011). Teaching students with moderate to severe disabilities. Guilford Press.

Browder, D., Spooner, F. & Ahlgrim-Delzell, L. (2011). Literacy. In D.M. Browder & F. Spooner. Teaching students with moderate and severe disabilities. (pp. 125-140). Guilford Press.

Cooper-Duffy, K., Hyer, G., & Sisk, P. (2014). Teaching Literacy with functional skills

to students with significant intellectual disability. Division on Autism and

Developmental Disabilities Online Journal, 37-55.

Cooper-Duffy, K., Szedja, P., & Hyer, G. (2010). Teaching literacy to students with cognitive disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43, 30-39.

Hudson, M. & Test, D. (2011). Evaluating the evidence base of shared story reading to promote literacy for students with extensive support needs. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 36(1), 34-45.

Hyer, G. & Cooper-Duffy, K. (2019). Preparing interns to use functional story-based instruction to teach students with significant intellectual disabilities in rural schools. Rural Special Education Quarterly. 1-14 https://doi.org/10.1177/8756870519826928

Jimenez, B. & Kemmery, M. (2013). Story-based lessons for students with severe intellectual disability: Implications for research-to-practice. Education Matters, 1(1), 80-89.

Koppenhaver, D., Hendrix, M., & Williams, A. (2007). Toward evidence-based literacy interventions for children with severe and multiple disabilities. Seminars in Speech and Language, 28, 79-89. doi:10.1055/s-2007-967932

Westing, D., & Fox, L. (2009). Teaching students with severe disabilities. (4th ed.). Merrill/Prentice Hall.