North Carolina’s Prospects for COVID-19 Economic Recovery: Top-down and Bottom-up Assessments

Emma Blair Fedison and Edward J. Lopez

Executive Summary

What are North Carolina’s prospects for making a sustained COVID-19 economic recovery? With a still-staggering labor market and economic hardships on the rise, state leaders have committed to the priorities of economic growth and prosperity. In this Brief, to assess the state’s prospects for sustained recovery, we focus on two main components: the state’s fiscal health and the state’s economic health. We review recent studies on North Carolina’s state budget to show how years of fiscal discipline have put the state budget in good condition. Next, we measure economic health by combining recent studies on economic freedom. We discuss many useful approaches to measuring the health of an economy, but economic freedom indexes are directly related to North Carolina’s stated objectives of promoting growth and prosperity, especially in rural areas. We find that North Carolina has created balanced improvements in the state’s economic climate. However, there is room for improvement, especially in worker regulations and market restrictions. Furthermore, the pandemic has altered the way the government regulates economic activity. Many of North Carolina’s COVID-19 economic policies today will be affixed into future measures and indexes of economic conditions. North Carolina currently lags behind Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia in these rankings. These indexes are known to correlate with economic growth and prosperity. Therefore, the decisions of today’s policymakers will affect the climate of COVID-19 economic recovery well into the future. North Carolina’s prospects for sustained recovery are good, underscoring the need to maintain good fiscal health and continue improving economic health in the state.

Introduction

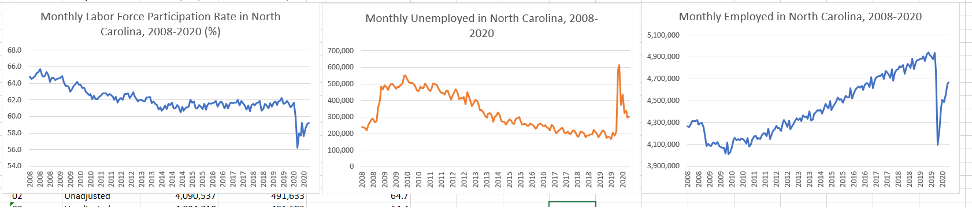

How poised is North Carolina for making sustained economic progress in a post-COVID recovery? The situation remains critical. Net job growth in North Carolina was just 1.1% during 2020, after factoring in the effects of the virus itself, the shutdowns, and the stimulus combined. This was the lowest annual rate since 2010 after the slow climb out of the Great Recession. As Figure 1 shows, the state’s labor market has only partially bounced back from the March 2020 shutdowns. More than a hundred thousand more Carolinians are unemployed in December 2020 compared to March. While jobs have also come back, total employment remains more than two hundred thousand below pre-pandemic levels, and labor force participation still lags two percentage points, currently at 59.2%. The number of Carolinians on SNAP benefits increased 20% from February to August, and currently, 35% of households report difficulty meeting ordinary expenses, while 18% report being late on rent. Some food banks in 2020 were serving up to five times as many families as the same time in 2019.[1] These problems are even worse in the vast rural areas of the state, and among underrepresented communities.

Figure 1: North Carolina Labor Market Conditions, 2008-2020

These policy initiatives are laudable in their intentions, and they support many meaningful achievements that might not otherwise be possible. However, these policies are not sufficient on their own for North Carolina to mount a sustained COVID-19 economic recovery. That is because these policies generally fall into a “top-down” category, while research in economics shows that “bottom-up” forces are crucial, irreplaceable ingredients to the human recipe for prosperity and flourishing.

Methodology

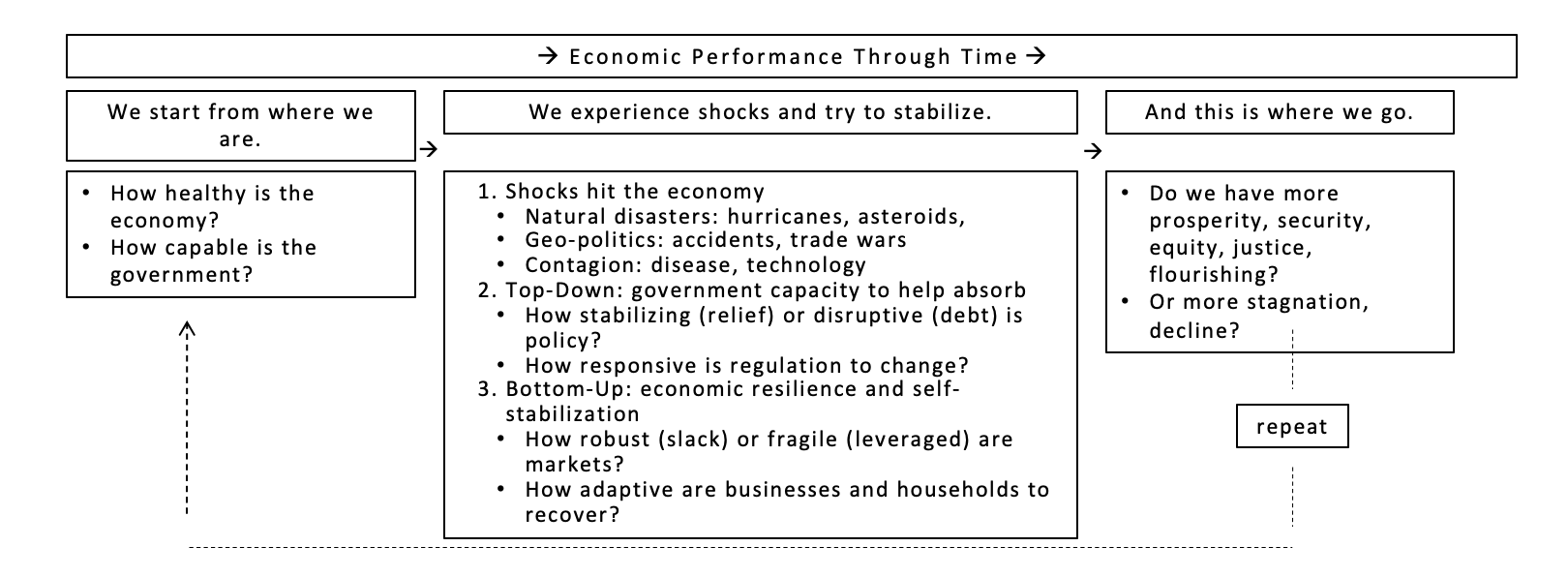

Think of the economy as an ecosystem of natural activity. Under good conditions, the ecosystem will thrive, and we will see richer combinations of biodiversity. But under adverse conditions, individual species will struggle, symbiotic interactions and cross-fertilizations will falter, and life in general will be less abundant or vibrant. When economists think about the economy in this evolutionary way, we use something like Figure 2 as guidance.

Figure 2: Economic Recovery over Time

But with large enough shocks, people’s lives get disrupted and governments are expected to respond with policies intended to absorb and stabilize things. This forms the top-down responses labeled #2 in the Figure. Meanwhile, ordinary people adapt their households, businesses, and communities in myriad numbers of ways known only at local levels. These responses comprise the bottom-up forces labeled #3 in the Figure.

Through time, these top-down and bottom-up adjustments to inevitable shocks play out over and over, and in good conditions, we experience a steady churn of creative destruction that hopefully washes out to economic growth and rising prosperity over time.

Quantitative researchers across many fields have devised different ways to measure the health of an economic ecosystem. Some approaches emphasize the underlying legal structure; for example, the American Bar Association’s annual Rule of Law Index measures protection of property and contract rights in its ranking of 128 countries. Similarly, the Cato Institute’s annual Index of Human Freedom measures protections of individual rights from both government and non-government sources of infringement. Other approaches emphasize the underlying culture: for example, the World Values Survey internationally, and the General Social Survey in the United States, both elicit public attitudes toward personal freedom and economic success. Still other approaches such as the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and the World Bank’s annual Doing Business report focus on the ease of business startups and failures. Researchers at Yale and the Urban Institute calculate an annual Economic Security Index to gauge people’s financial vulnerability. A German think tank publishes an annual Social Justice Index that combines metrics from environmental, economic equality, and poverty dimensions. The list of researchers measuring different aspects of an economy’s health goes on.

When it comes to North Carolina’s goals for growth and prosperity, economic freedom indexes are the most important among all barometers of economic prospects for growth, especially bottom-up growth. In the rest of this study, we follow the approach in Figure 2 to assess North Carolina’s prospects for COVID-19 economic recovery. First, we assess the top-down capacity by taking stock of the state’s current budget situation. Next, we will assess the bottom-up prospects by updating the most recent indexes of economic freedom in North Carolina, both at the state level and by drawing on information from very recent studies, also the municipal level.

North Carolina’s Budget Coming into the COVID-19 Pandemic

To measure government capacity in Part #2 of Figure 2, we will provide a brief update on North Carolina’s fiscal condition. Thankfully, North Carolina’s fiscal house appears to be in good order, although this has not always been the case. Coming into the pandemic, North Carolina boasted a buffer of nearly $6 billion in cash, including $1.2 billion in its rainy day fund, $2.9 billion in its unemployment insurance fund, and $1.5 billion in other department funds. In contrast, 36 other states have smaller rainy day funds.

These reserves had been built up over time through fiscal restraint, a growing economy, and a gradual strategy to phase-in corporate and income tax rate reductions. Prior to the pandemic, North Carolina was on its way to its sixth straight year of budget surplus under a planned 16% total growth in state spending over eight years up to 2020. Total state debt decreased by 35% from $6.5 billion in 2010 to $4.2 in 2020, freeing millions in saved debt service expenditures for other expenditures.

By contrast, entering the Great Recession the state’s capacity was much lower and posed a major disadvantage to recovery. The rainy day fund was only $800 million in 2008 and it barely lasted a year. The state had to borrow more than $2.8 billion in federal funds to meet its unemployment claims. Declining revenues upset a planned 49% increase in spending over eight years; instead the state suffered through rising deficits and mounting debt amid government employee layoffs and furloughs.

Thankfully these kinds of disturbances have so far been avoided since the onset of the 2020 pandemic, as Governor Cooper has drawn on hard-saved taxpayer reserves to cushion the blow. Despite the sharp decline in sales and gas taxes (a potential 10% drop in revenue), NC’s finances remained strong heading into 2021. With this better fiscal buffer, North Carolina had a high government capacity to confront the shock of COVID-19 and restrictions.[1]

What is Economic Freedom and Why is it Important?

The connection between economic freedom and prosperity traces back to the founding father of economics, Adam Smith, and his 1776 classic, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Until roughly the time of Smith, people had historically lived mostly poor lives. Smith and his contemporaries took note of how life proliferated when people traded with each other on a large scale, in particular across great distances and national borders.

Illustrating with his famous examples—the pin factory, the woolen coat, the invisible hand—Adam Smith launched the idea that the key to prosperity is the freedom to specialize and trade, or what he called a society’s “system of natural liberty”. Building an economy on the principle of natural liberty means allowing individuals the autonomy to engage and specialize in their own pursuits, free from undue restrictions. Freeing people to pursue their own individual projects not only results in personal empowerment and human dignity, Smith argued, it also unleashes the economic forces of specialization and exchange, which together lead to innovations, many of which will fail, but some of which will fuel the prosperity of great masses of people. Economists from Karl Marx to Paul Krugman have been trying to figure out this idea ever since.

Economic Freedom in North Carolina and Neighboring States

To modern economists, economic freedom can be measured with government policies that affect the economic climate. These measurements can then be compared to equivalent measurements in different places and times. Economic freedom indexes at the international and state levels have been published annually going back decades. Now, within the past few years, an emerging offshoot of this literature is generating indexes of economic freedom at the metro/micropolitan and local/regional levels as well.

Calculating these indexes is straightforward. Researchers first identify measurable policies that affect economic freedom and then categorize them into very broad areas, such as labor market regulations or tax policy. Next, researchers measure as many specific policies within those broad areas as they can, such as occupational licensure or the highest marginal tax rate. Finally, researchers assign scores to individual policies and then take a weighted average to get a single score. Most economic freedom indexes scale their scores from 1 to 10, but not all do.

The annual Economic Freedom of North America (EFNA) report measures state policies and calculates an index of support for economic freedom.[2] Each state is assigned a score between 1 and 10 that represents a composite of ten separate measures organized into three policy areas: government spending, tax competitiveness, and worker regulation. Calculating the index is as simple as gathering the reported data and taking a weighted average. The EFNA calculates annual scores dating back to 1984, with 2018 being the most recent year of data published in the 2020 report.

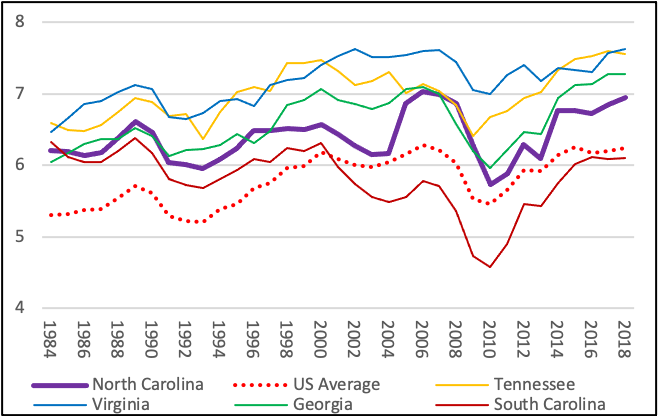

Figure 3: North Carolina and Neighboring States

Economic Freedom of North America (EFNA) Scores, 1984-2018

Figure 3 helps us visualize how North Carolina’s economic climate has changed over time, and how it compares to both neighboring states and the national average. In the most recent (2020) EFNA report, North Carolina’s overall score is 6.95 out of 10, compared to the national average of 6.25, for a ranking of 11th out of the 50 states. This ranking is substantially up compared to low points in 2002-03 (about 25th) and 2011-13 (about 20th). During those stretches, North Carolina’s economic policies were in bad shape, and the EFNA index reflected that.

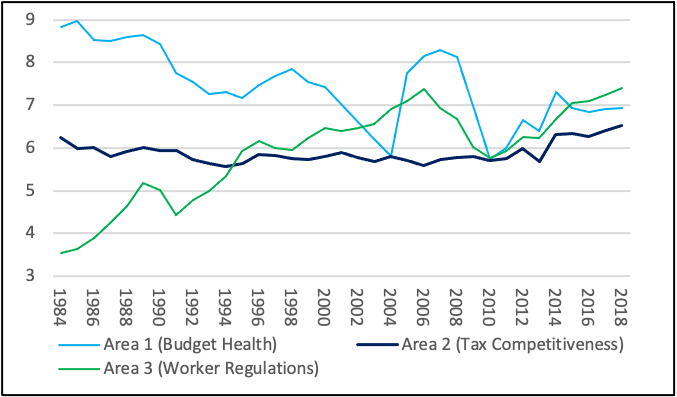

Figure 4: Sub Areas of North Carolina

Economic Freedom of North America (EFNA) Scores, 1984-2018

Source: Author’s graph using information from Stansel et al (2020).

What is driving North Carolina’s improved economic freedom ranking over the past decade? Figure 4 breaks down the EFNA scores into the three policy areas of the index. Looking first at Area 1 (budget health), the low points of 2002-03 and 2011-13 are visible as sharp downturns in the Area 1 component. But for nearly the past decade, the Area 1 component has increased as the state’s fiscal house improved. In addition, the last decade also shows increases in Area 2 (tax competitiveness) and Area 3 (worker regulations). This means that North Carolina’s rise in the overall index has been a relatively balanced one: it has been driven by increases in all three measured policy areas.

Table 1 lets us compare recent rankings to neighboring states in the southeast. This information shows that North Carolina’s regional economic freedom ranking is a mixed bag. On the one hand, North Carolina consistently outranks South Carolina, and this difference may be widening over the years. The Tarheel state also sits pretty comfortably above the national average.

On the other hand, North Carolina lags behind Georgia, Tennessee, and especially Virginia. Over the past two decades, Tennessee has not ranked outside the top 10 except once, Virginia has never ranked below 6th, and Georgia has stayed at 16th or better and has a four-year streak ranked among the top 7. Meanwhile, North Carolina has bounced up and down, slumping as low as 25th in the nation. But again, the last decade has seen policies that improve the economic climate in North Carolina, and the EFNA index has reflected that as well.

Table 1: Score and Rank out of 50 on Economic Freedom of North America (EFNA) Index,

NC and Neighboring States, 2001-2018

| U.S. Average | NC Score | NC Rank | SC Score | SC Rank | GA Score | GA Rank | TN Score | TN Rank | VA Score | VA Rank | |

| 2018 | 6.25 | 6.95 | 11 | 6.11 | 30 | 7.27 | 7 | 7.55 | 5 | 7.62 | 3 |

| 2017 | 6.21 | 6.85 | 12 | 6.09 | 30 | 7.27 | 6 | 7.60 | 3 | 7.57 | 4 |

| 2016 | 6.17 | 6.73 | 14 | 6.11 | 29 | 7.13 | 7 | 7.53 | 3 | 7.31 | 6 |

| 2015 | 6.25 | 6.77 | 16 | 6.01 | 32 | 7.13 | 7 | 7.48 | 5 | 7.33 | 6 |

| 2014 | 6.14 | 6.76 | 14 | 5.75 | 33 | 6.95 | 11 | 7.33 | 6 | 7.37 | 5 |

| 2013 | 5.93 | 6.10 | 22 | 5.42 | 34 | 6.44 | 13 | 7.02 | 6 | 7.18 | 4 |

| 2012 | 5.93 | 6.30 | 19 | 5.46 | 31 | 6.47 | 14 | 6.94 | 8 | 7.40 | 3 |

| 2011 | 5.66 | 5.89 | 20 | 4.89 | 40 | 6.22 | 14 | 6.76 | 7 | 7.26 | 2 |

| 2010 | 5.47 | 5.74 | 19 | 4.58 | 43 | 5.97 | 15 | 6.68 | 4 | 7.00 | 3 |

| 2009 | 5.53 | 6.26 | 13 | 4.73 | 41 | 6.20 | 15 | 6.41 | 8 | 7.06 | 3 |

| 2008 | 6.03 | 6.86 | 8 | 5.36 | 38 | 6.58 | 16 | 6.84 | 9 | 7.44 | 4 |

| 2007 | 6.22 | 6.99 | 12 | 5.71 | 33 | 7.00 | 11 | 7.04 | 9 | 7.62 | 3 |

| 2006 | 6.28 | 7.04 | 12 | 5.78 | 34 | 7.10 | 11 | 7.14 | 7 | 7.61 | 3 |

| 2005 | 6.16 | 6.86 | 13 | 5.56 | 39 | 7.07 | 9 | 7.01 | 11 | 7.54 | 3 |

| 2004 | 6.05 | 6.17 | 25 | 5.49 | 37 | 6.87 | 11 | 7.31 | 7 | 7.51 | 3 |

| 2003 | 5.98 | 6.15 | 24 | 5.55 | 34 | 6.79 | 11 | 7.18 | 6 | 7.52 | 2 |

| 2002 | 6.00 | 6.28 | 21 | 5.74 | 32 | 6.85 | 11 | 7.12 | 7 | 7.62 | 2 |

| 2001 | 6.09 | 6.43 | 18 | 5.98 | 28 | 6.91 | 10 | 7.32 | 6 | 7.54 | 3 |

Authors’ table based on Stansel et al. (2020).

There are limitations to the information provided by the EFNA scores and rankings. For example, the index does not include land-use policy, which is especially important at micro levels of bottom-up development. Nor does it pick up the strong network of regional and county economic development authorities in the state. Keeping these limitations in perspective is important. All approaches to measuring the economic climate provide useful indications, but none is intended to provide a complete picture.

For comparison purposes, another state-level economic freedom index is the Cato Institute’s Freedom in the 50 States: An Index of Personal and Economic Freedom (F50), published annually.[1] This index covers a very broad range of policies, calculating a weighted average of 230 distinct state policies, in each state and in each year. North Carolina ranks #18 out of the 50 states on the overall composite score in the most recent edition of the F50 index, reflecting data up to 2018. The state has fallen three spots since its #15 ranking in the 2014 data.

Table 2: Specific Policy Areas for Improvement in North Carolina’s Economic Climate

| Area | Policies | Ranking |

| Market Entry Restrictions |

Certificate of need laws for medical facility, household goods movers, other market producers Independent commission review of new occupational licensure legislative proposals Strict rules on distribution, consumption, pricing in gasoline, alcohol, and other retail goods |

#37 on Freedom from Cronyism component Negative score on alcohol freedom |

| Price Restrictions |

Personal automobile and homeowner insurance, strict price, and rate classification controls Price-Gouging laws strict and used frequently |

#21 on Regulation component |

| Occupational Freedom |

Strict rules on physician assistants, nurse practitioners, paramedics, dental hygienists, other health professionals Lowest possible rank on nurse practitioner independence, NC is not a member of the Nurse Licensure Compact, permitting multistate practice |

#37 on Occupational Regulation component |

Source: Authors’ summary of information in Ruger and Sorens (2018)

Table 2 shows how the F50 index is especially valuable for looking at specific policy areas that need improvement to ensure a healthy economic climate. The authors of the index count these policies as “blatantly anti-competitive regulations”. This means that the policies restrict ordinary people’s abilities to control their economic lives while also failing to serve a demonstrable public interest. In some cases of price and entry regulations, the policy appears primarily to enrich privileged incumbents by limiting competition.

Economic Freedom in North Carolina’s Cities: Raleigh, Charlotte, Greensboro, Asheville

Researchers in recent years have started calculating economic freedom indexes at the local level. For example, the Doing Business North America report (DBNA) ranks 130 cities in the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The rankings are a composite measure of 111 separate measures of the ease of performing business activities across six broad categories: (1) starting a business, (2) employing workers, (3) getting electricity, (4) paying taxes, (5) land and space use, and (6) resolving insolvency. In the report’s second year, the 2020 DBNA includes Raleigh, Greensboro, and Charlotte.

Another recent local index is the annual Metropolitan Area Economic Freedom Index (MEFI).[2] This study ranks metropolitan (large) and micropolitan (small) cities on a composite score across nine policies measured in three main areas: budget health, tax competitiveness, and worker regulation.

As Table 3 summarizes, Raleigh tops the 2020 list of most economically free large cities on the entire list, ranking #1 in the “ease of doing business” category with a score of 82.42. Greensboro is ranked 35th with a score of 75.13, with Charlotte following closely in 38th place and a score of 74.88. Among the smaller cities, Jacksonville and Durham-Chapel Hill rank relatively highly at #38 and #66 respectively. In the middle of the pack is Winston-Salem at #95 overall. And lagging behind are Goldsboro at #109 and especially Asheville, whose economic climate ranks near the bottom of the index at #133.

Table 3: Economic Freedom in Select North Carolina Cities

| Metro Area Economic Freedom Index 2019 | Doing Business North America 2019 | Doing Business North America 2020 | ||||

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | |

| Raleigh | 7.19 | #15 | — | — | 82.42 | #1 |

| Charlotte | 6.69 | #30 | 82.97 | #6 | 74.88 | #38 |

| Greensboro | 6.83 | #103 | — | — | 75.13 | #35 |

| Jacksonville | 7.43 | #38 | — | — | — | — |

| Durham-CH | 7.17 | #66 | — | — | — | — |

| Winston-Salem | 6.88 | #95 | — | — | — | — |

| Goldsboro | 6.79 | #109 | — | — | — | — |

| Asheville | 6.67 | #133 | — | — | — | — |

Source: Authors’ compilation from the listed studies. The — marks indicate no data.

One reason for the policy relevance of these scores is that they correlate with entrepreneurial activity. A 2020 study published in Small Business Economics breaks down the MEFI and shows how sub-components relate to business starts and closures. Among the study’s findings, cities with high property taxes and minimum wage mandates have lower business entry and higher business exit rates. Cities with more generous welfare benefits and greater private-sector union representation have lower firm exit rates.

Conclusion: Policy Implications for Discipline, Freedom, and Balance

North Carolina’s economic prospects under COVID-19 depend on two crucial factors: the state having a strong capacity for top-down relief and the people having a healthy climate for bottom-up recovery. For these reasons, fiscal discipline and rising economic freedom should remain at the top of policymakers’ priorities. The state’s economic policymakers have been doing an admirable job on these two factors for about the past decade, and these hard-fought efforts have allowed North Carolina to establish effective strongholds, not only to absorb the shock of COVID-19 but also to clear paths for ordinary people to move forward with rising prosperity and flourishing for all.

Our analysis does not support specific policy recommendations. For example, we do not offer a basis for leaders to make the best choice on minimum wage laws, marginal tax rates, or price and entry regulations. Future research into these particular policies can provide more granular evidence for policy consideration.

As for this study, our analysis here supports three broad policy conclusions

1. North Carolina must continue to keep its fiscal house in good condition. The pains of 2002-03 and 2011-13 are still powerful reminders of the need to make only sustainable commitments to future spending plans. This is a difficult task because fiscal discipline carries its own painful choices. Just ask those in the state who have been clamoring about teacher pay, roads, prisons, and Medicaid expansion. Or just come visit the hallways of the UNC System, where faculty salaries have stagnated for a decade. Yet fiscal discipline is vitally important to avoiding the very great dangers of the state budget being in poor health when major shocks come along in the future – and they inevitably will. So far, we have been able to avoid the tremendous pains of layoffs and furloughs. To promote their stated goals of growth and prosperity for COVID-19 economic recovery, policymakers should double-down on their efforts to maintain a well-prepared fiscal house.

2. Protect economic freedom. Policymakers should strive to maintain economic freedom as a priority in the state’s economic policies. Doing so empowers Carolinians to pursue their own achievements while improving each other’s lives. Doing so also tends to generate socially good results. A large body of research shows how economic freedom coincides with beneficial measures of economic development, including job creation, income growth, and a host of quality-of-life measures including life expectancy, literacy rates, lower child labor participation, more gender equality, and more. For North Carolina, as people seek to work together to achieve the best possible economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, economic freedom will continue to play a key role

3. Maintain balanced freedom across the state’s portfolio of economic policies. New research in economics and entrepreneurship studies shows that growth and prosperity do better when economic freedom is protected with balance across the measured policy areas.[3] The idea is, if two neighboring states both have overall composite scores of 7 out of 10, then the state with a more balanced path of getting to the overall 7 will do better. For example, North Carolina’s overall composite EFNA score is 6.95 while South Carolina’s is 6.11. Yet as we mentioned earlier, North Carolina has improved its scores in all three areas of the EFNA index over the past decade, and can now balance even further by scrutinizing certain occupational and retail restrictions. South Carolina’s problem is it ranks very low on one of the three policy areas (budget health), while ranking better in the other two. According to our calculations, this makes South Carolina’s policies about 17% less balanced compared to North Carolina’s.[4] Clearly, the low score on South Carolina’s fiscal health is a disadvantage to its prospects, according to the analysis in this paper. For the same reasons, North Carolina’s advantage is improved by maintaining balanced economic freedom.

In summary, our combined top-down and bottom-up assessment suggests a policy rule: when policymakers determine that the public interest justifies curtailing people’s economic freedom in some area of economic policy, recognize that doing so decreases the state’s prospects for COVID-19 economic recovery, and then search for changes elsewhere in the policy portfolio that might raise people’s economic freedom in those areas without undue compromise to the public interest. Doing this would maintain a high level and good balance of economic freedom across the state’s portfolio of economic policies. Finding these other policy areas can also be hard work. Many times it can involve modernizing an older set of regulations, or revising legislation that was introduced in bygone economic times, depending on evidence-based research that shows the intended and actual impacts of policies. For example, price and entry restrictions that serve primarily to protect incumbents warrant scrutiny under a public interest standard. Future research can shed more light on where these specific policy areas lie.

In conclusion, North Carolina’s prospects for making a sustained COVID-19 economic recovery are good. Policymakers should be recognized for these hard-fought achievements. Moving forward, the goals of North Carolina’s leaders for growth and prosperity are well-served if they can maintain and sustain a healthy budget for top-down capacity and a healthy economy for bottom-up growth.

Footnotes:

[1] Ruger and Sorens (2020).

[2] Stansel (2020).

[3] For the importance of policy balance when making international country comparisons, see Bolen and Sobel (2020), and at the local level see Bennett (2020).

[4] The two states’ scores on Areas 1-3 respectively are North Carolina (6.94, 6.53, 7.39) and South Carolina (5.01, 6.18, 7.13), which on a percentage share basis converts to (0.333, 0.313, 0.354) and (0.302, 0.284, 0.321) respectively. Using a standard measure of concentration known as a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, where greater numbers indicate less balance, we calculate NCHHI = 3341.84 and SCHHI= 3400.53. This indicates that South Carolina’s three policy areas on the EFNA are 17.56% more unbalanced as compared to North Carolina’s same policy areas.

About the Author

Emma Blair Fedison (emmablair2015@gmail.com) is a policy researcher for CSFE. She is completing her master’s in economics and the Mercatus Center’s MA Fellowship at George Mason University this spring. Edward Lopez (ejlopez@wcu.edu) is a Professor of Economics and Director of CSFE at Western Carolina University. Follow him at enterprise.wcu.edu and @csfe_wcu.

References

- Balfour, Brian. 2020. “A tale of two recessions: Conservative budgeting has NC far better prepared to weather COVID recession compared to Great Recession.” Civitas Institute https://www.nccivitas.org/2020/tale-two-recessions-conservative-budgeting-nc-far-better-prepared-weather-covid-recession-compared-great-recession/

- Bennett, Daniel. L. 2020. “Local institutional heterogeneity & firm dynamism: Decomposing the metropolitan economic freedom index.” Small Business Economics https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00322-2

- Bolen, J. Brandon and Russell S. Sobel. “Does Balance Among Areas of Institutional Quality Matter for Economic Growth?” Southern Economic Journal 86(4), pp.1418-1445

- Frank, Peter M. 2018. “State Tax Policy and Growth: A Research Note.” Political Economy in the Carolinas 1, p. 112-118. http://www.classicalliberals.org/pec-volume-1/

- Hacker, Jacob s., Gregory A. Huber, Austin Nichols, Phillip Rehm, Mark Schlesinger, Rob Valletta, and Stuart Craig. “The Economic Security Index: A New Measure for Research and Policy Analysis,” Review of Income and Wealth 60 (May), pp.S5-S32

- Lawson, Robert A. “Economic Freedom, What is it Good For?” CSFE Issue Briefs 4(1), pp.1-10 https://affiliate.wcu.edu/csfe/2019/04/22/economic-freedom-what-is-it-good-for-robert-a-lawson-ph-d/

- Gwartney, Robert A. Lawson, Joshua C. Hall, and Ryan Murphy, Economic Freedom of the World 2020 Report, www.freetheworld.com

- Murphy, Kate. “Triangle food banks losing federal support, but demand is still soaring due to COVID-19,” The News & Observer, December 19, 2020, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/article247704980.html

- Center on Budget Policy and Priorities, “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships,” COVID Hardship Watch, Updated January 8, 2021

- Ruger, Will and Jason Sorens. 2018. Freedom in the 50 States: An Index of Personal and Economic Freedom. Cato Institute.

- Rural Economic Development Division. 2020. “Engaging, Enhancing, and Transforming Rural North Carolina,” North Carolina Department of Commerce, undated https://files.nc.gov/nccommerce/documents/Rural-Development-Division/REDD-Annual-Report_final.pdf

- Stansel, Dean. 2020. Metropolitan Area Economic Freedom Index, Fraser Institute. https://www.smu.edu/cox/Centers-and-Institutes/oneil-center/research/U,-d-,S,-d-,-Metropolitan-Area-Economic-Freedom-Index

- Stansel, Dean. 2013. “An Economic Freedom Index for US Metropolitan Areas,” Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy 43(1), pp.3-20.

- Stansel, Dean, José Torra, and Fred McMahon. 2020. Economic Freedom of North America 2020, Fraser Institute. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom-of-north-america-2020

- Vásquez, Ian and Fred McMahon. 2020. The Human Freedom Index 2020, Cato Institute.

Further Readings

For more background on the role of economic freedom in a flourishing society, see our 2019 CSFE Issue Brief on this topic written by Robert Lawson, one of the lead authors of the annual Economic Freedom of the World report (Lawson 2019). At the state level, Dean Stansel’s paper in the Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy (Stansel 2013) provides the analysis underlying the EFNA Prominent indexes of freedom at the international level include Gwartney et al (2020), Vásquez & McMahon (2020). The works of Adam Smith, including his most famous book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, are available free online at EconLib.org, the Library of Economics and Liberty. Bestselling science author Matt Ridley’s How Innovation Works and Why I Flourishes in Freedom (Ridley 2020) provides an engaging account.